The conundrum of a winning player who impacts the game beyond the box score—but whose team also needs him to stuff the stat sheet

On Sunday night against Denver, the Pacers did something they had previously done only five times in 25 tries since Tyrese Haliburton joined the team: win when their best player scored in single digits.

As Tyrese’s trainer was quick to point out after the game, “When you watch games, it’s obvious how valuable @TyHaliburton22 is. Impacts winning beyond box score numbers.” He’s right; it is obviously true.

But there’s a catch: The Pacers need their offensive engine to stuff the stat sheet and provide his obvious and unmeasurable impact for them to be at their best. In games this season when Haliburton has filled up his box score, the Pacers almost always win. When he doesn’t, they usually lose. And the team’s performance appears to depend on his statistical output more than any other playoff-bound team relies on its star.

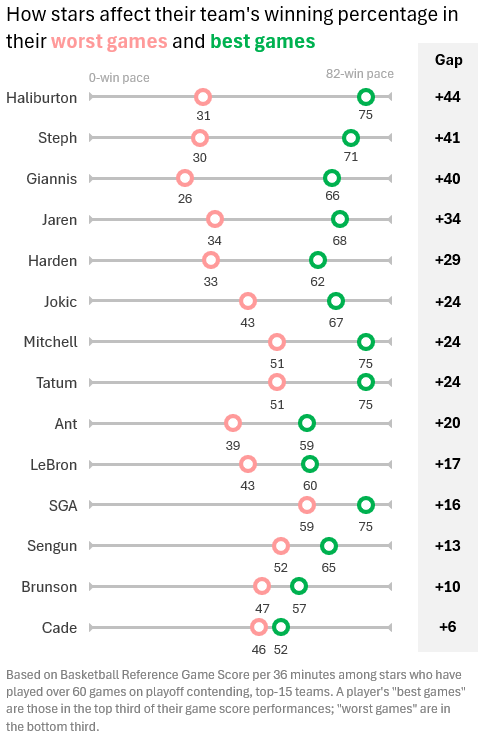

In Haliburton’s best box score games this season, the Pacers have played like a 75-win team. In his worst, the Pacers have played like a 31-win team—a gap of 44 wins, the largest gap in team performance for any of the playoff-bound stars this year. Indiana swings from winning games by 15 on average, to losing them by 6—again, the largest such swing among the fourteen stars shown.

We can take this a step further: The same pattern emerges looking only at scoring, that most reductive measure of basketball impact. The Pacers’ win pace in Haliburton’s highest-scoring games is 27 games better than in his lowest-scoring games—again, the widest gap in this group.

Indiana’s reliance on Haliburton stands apart from their playoff-bound rivals. Oklahoma City, Boston, Cleveland, Houston, and New York (not coincidentally, the league’s five best teams this year) are much better when their stars shine, but they also hold up just fine when they don’t. This is a testament to their top-level talent and their depth.

Indiana hasn’t found the same balance. Pascal Siakam’s metronomic performances have, in this specific way, held the team back. He is consistent, but he has not compensated for Haliburton’s off nights. When Tyrese has scored in single digits this year, Pascal has averaged 21 points per 36 minutes; on all other nights the two of them shared the court, he has averaged 22.

The rest of the team hasn’t picked up the slack. Over the last two seasons, when Tyrese has a high-scoring game, the rest of the team, on average, posts a 58% eFG%; when he has a low-scoring game, they shoot a nearly identical 57%.

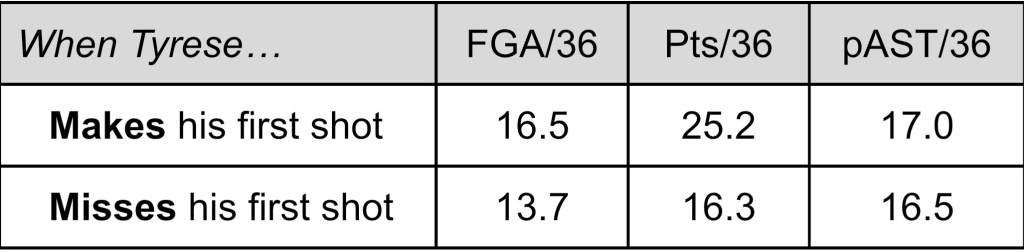

Some nights this season, Tyrese has taken himself out of games. When Tyrese has made the first shot he’s taken, he’s gone on to take more shots, score more, and shoot more efficiently the rest of the game. When he misses his first shot, he does the opposite.

“It’s been an up and down year for me offensively. There’s been a lot of games where I might not have asserted myself enough or just overthinking not shooting enough, passing up good shots,” Haliburton said after a game in February. “… People say low lows and high highs. I feel like I’ve had a lot of low lows and not high highs, just like whatever is in the middle. I feel like I haven’t had many games this year where I feel like I was really good offensively.”

Haliburton has talked about how he wants to keep shooting when he’s on a heater, but the issue comes on the other side, in games where missing early leads him to shoot less. And he isn’t fully replacing that scoring production with passing: the point guard is averaging 17 potential assists per 36 when he makes his first shot this year vs. a nearly identical 16.5 when he misses it.

This is an appropriate pattern for a role player, but not a star. And with a Pacers bench that has been inconsistent this season, Haliburton cannot count on the second unit picking the starters up like they used to. For the team to succeed in the playoffs and reach the heights of playing into May and June that Tyrese has talked about, he will have to lead the way—impacting the game in all the ways you can’t measure, while also dominating in all the ways you can. That is the burden of being a superstar.

This seems a bit arbitrary and conveniently doesn’t include the stat that Haliburton’s trainer was QT-ing. With the exception of the games against Portland, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Denver, all of the games that he scored in single-digits came in the first few months of the season. Camara was awesome, Haliburton didn’t play in the second half against Cleveland, and Denver was consistently doubling him. There are games this season when he certainly could’ve been more aggressive (e.g. home loss to Oklahoma City), but this makes it seem as though there are no other factors in the outcome of those games or his shot-volume than whether he makes his first shot. His passing and defense were also affected by his early season limitations. The competitive passes he makes out of traps/blitzes aren’t always going to register as “potential assists” because of how often this team makes two additional passes in those situations. Needs more context.

LikeLike

That most of these low-scoring performances occurred earlier in the season is very much the point — this level of inconsistency is the point. Many other stars aren’t this inconsistent, and their teams haven’t gone through such feast or famine periods accordingly. The team’s turnaround didn’t just happen to coincide with Tyrese’s turnaround; it was driven by it, it required it. The whole point of this article is that we have a conundrum: Tyrese is a guy who makes the right play nearly all the time, in ways that sometimes show up in the stats and sometimes don’t, just like you’re saying. AND YET: the team’s performance swings more wildly with his ability to put the ball in the hoop and fill up the stat sheet than *any other playoff-bound star.* That’s kinda nuts! I think it’s interesting and fairly surprising that he stands out this way, but to each their own. My hypothesis is that he is a rhythm player, both because that’s what it looks like — strong positive and negative feedback loops where good play begets more good play and vice versa — and because he’s talked about this, how when he sees a couple shots go in he knows it’s his night and he wants to keep shooting. The ‘first shot’ data point is one attempt to test that hypothesis.

LikeLike